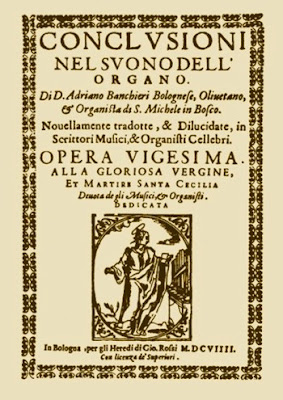

Organi di somma perfettione: Italian Organs, Organists and Organ Builders, mentioned by Adriano Banchieri in his Conclusioni nel suono dell'organo (Bologna, 1609)

Among the most important academic works on organs and organ music written in Italy during the late-Renaissance and early-Baroque period, Adriano Banchieri’s Conclusioni nel suono dell’organo, is considered one of the greatest sources of information about the church music scene of his time. In this book, where every chapter is called Conclusione, Banchieri names the most famous Italian organists, organ builders and organs of the time, capturing reality on paper from his scholarly and erudite point of view. We will focus on Conclusioni number four and five, where he presents the most historical information about his contemporaries that we are going to consider in this essay.

The Olivetan friar Adriano Banchieri (Bologna, 1568-1634) – baptized with the name Tommaso Banchieri – belonged to the convent of San Michele Bosco in Bologna, which he joined in 1587. From 1592 he was a student of Gioseffo Guami and in 1596 he began his service as organist at his convent in Bologna. He was active as an organist in many different cities: Imola (Santa Maria in Regola church, 1600), Gubbio (San Pietro church, 1604), Venice (Sant’Elena church, 1605), Verona (Santa Maria in Organ church, 1606). In the archives of Monte Oliveto Maggiore Abbey, Siena, the organist, documented as Reverend Adriano of Bologna, is none other than Banchieri himself, who relocated to Siena, becoming the first organist to have served on the new organ built by Cesare Romani in 1606. Banchieri’s first version of his Conclusioni – lost today – was published in Siena in 1608: this proves that Banchieri served as an organist at the famous abbey for a few years, before moving to Bologna again in 1609, where the second version – the one we know today – was published. One of his most important academic works is L’Organo suonarino, published in Venice in 1605 as opus 13, then reprinted as opus 25 (Venice, 1611) and again as opus 43 (Venice, 1622 and 1638). He often travelled to learn about the great musical innovations of Italy: in fact, with his many musical, theoretical, didactic and literary works, he is considered one of the most active composers and scholars of his time.

With a sonnet dedicated to Saint Cecilia, patron saint of church musicians, the Olivetan monk Adriano Banchieri begins his book titled Conclusioni nel suono dell’organo – meaning “Conclusions on the Sound of the Organ” – published in Bologna by the heirs of the typographer Giovanni Rossi (1556-1595) in 1609. After this short introduction, Banchieri explains the origins of the devotion to Saint Cecilia, remembering how in many places in Italy some religious services are celebrated in memory of the saint. Banchieri describes how every year in Siena on November 22, a solemn mass is celebrated at the Cathedral together with the local musicians and organists: he was present himself at the service on November 22, 1596 – “[…] ond’io dodeci anni sono mi ritovai presente […]” – celebrated by the Archbishop of Siena, Ascanio Piccolomini (1548-1597). The liturgy featured a great number of musicians – “[…] la quale fu concertata con grandissimo concorso di virtuoso ridotto […]” – directed by the chapel master Andrea Feliciani and accompanied by the organist Francesco Bianciardi, who had both recently died and were highly esteemed by Banchieri, who wishes heavenly grace to their souls – “[…] essendo maestro di capella, & Organista Andrea Feliciani, & Francesco Bianciardi, le cui anime sieno à godere il frutto, & e merito in Paradiso. […]”.

There is very little biographical information about the Sienese composer Andrea Feliciani (ca.1550-1596), a man of humble origins as stated by Feliciani himself in his Liber Primus Missarum (Venice, 1584) – “[…] homo privatae fortunae ac humilis originis […]”. In December 1757, he became chapel master at Siena Cathedral, where he stayed until 1596. Feliciani died on December 24, 1596, and was succeeded by Francesco Bianciardi, his former assistant as cathedral organist. He published masses, motets and secular music in the style of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594), the most representative composer of the Renaissance polyphony, who probably was the teacher of Feliciani.

Francesco Bianciardi (ca.1570-1607) – also known as Bianchiardus, Biaciardus or Blanchardus – was born in Casole d’Elsa, a picturesque town nestled between the rolling hills of Siena. We still have little information about Bianciardi’s training and we do not know with whom he studied music during his early years: the first records date back to 1596, where he appears as organist at Siena Cathedral, of which he also became the chapel master the following year. Member of the Accademia degli Intronati, he rose to the head of the academy in year 1601. He died young during a plague in Siena before September 21, 1607. Bianciardi was a composer and organist appreciated by many contemporaries but his music is very little known today: his motet Ave Rex noster is rememebered by the Austrian-Czech musicologist August Wilhelm Ambros (1816-1876) as “a splendid work of great purity […] containing beautiful harmonies”. Author of both secular madrigals and sacred motets, he was an author of fine sensitivity and among the first to use numbered bass: his last academic work, published posthumous in Siena in 1607, was a list of advices about how to play the continuo – Breve regola per imparar a sonare sopra il basso (Siena, 1607). Bianciardi composed only a few keyboard pieces: six Ricercari and four Fantasias were published in 1977 by the American Institute of Musicology in the Corpus of Early Keyboard Music Series, volume 41, edited by Bernhard Billeter and Hässler-Verlag.

Continuing with his account, Banchieri describes Saint Cecilia’s day in Milan, where the local musicians celebrate a solemn mass at Santa Maria della Scala ducal church, and in Ferrara, where the same kind of service is celebrated at Santa Maria in Vado church. The author concludes the first part about the cult of Saint Cecilia with the hope that other musicians will follow the examples in Siena, Milan and Ferrara, “leaving the transitory concerts of this worldly life […] to enjoy those in the other end who will never end” – “[…] acciò che tutti gli professori à lei devote, nel lasciare gli concerti transitorij di questa mondana vita, sieno fatti degni nell’altra godere in sempiterno quelli, che mai hanno fine […]”.

After the second Conclusione which describes the other kind of organs invented by the ancient populations – Organi da gl’antichi diversamente inventati – and the third one about the ancient organ history – Inventore, & introduttione dell’Organo con mantici – the fourth Conclusione names the most famous organs, organists and organ builders of his time – Organi, Organisti, & Organari cellebri, à gli tempi moderni.

The first name mentioned by Banchieri in this fourth Conclusione is Vincenzo Fiamengo, but he will talk more about his work in the fifth Conclusione, and consequently we will consider him later.

Gubbio Cathedral (Umbria), a large 13th century church with an impressive wagon-vaulted ceiling, had a most stupendous instrument played by Girolamo Diruta – “[…] Nel Duomo di Ugubbio ritrovasi un Organo stupendissimo, suonato da Girolamo Diruta […]”.

This large instrument was built in 1548 by Luca di Bernardino (ca.1490-1551) assisted by his nephew Agostino di Bartolomeo Cianciulla (?-1572), both from Cortona (Tuscany). The commission agreement gives some information about this large organ, based on a 12-foot principale – “[…] de altezza de undece piedi la canna principale […]” – with a 47-key manual from FF to f2 without FF# and GG# - “[…] de tasti quarantasette intra bianchi et negri, incomenzando al fa et finendo similiter in fa […]” – with 7 stops, the principale made of tin and the others made of lead – “[…] cum septe registri, videlicet: il principale de stagno et li altri di piombo […]”, and 4 large bellows – “[…] cum mannici quatro […]”.The original disposition is not reported in the document, but could be hypothesized as the following, according to the larger Luca di Bernardino organ at Arezzo Cathedral built between 1534 and 1536:

Principale 12, Ottava 6, XV, XIX, XXII, XXVI, Flauto in VIII 6.

The cathedral organist between 1604 and 1610 was the famous Girolamo Diruta (ca.1550 – after 1613), born in the small village of Deruta, Perugia (Umbria) – but he used to introduce himself as a Perugia citizen. He was a Franciscan friar, first at the Franciscan convent in Correggio then in Venice. In 1580 he published his only sacred music collection, Il primo libro de’ contrapunti sopra in canto fermo delle antifone […] (Venice, 1580), now partially lost. When organist at Chioggia Cathedral, nearby Venice, Diruta published in 1593 the first part of his most famous work, Il Transilvano, a theorical-practical treatise on the study and practice of keyboard instruments including original compositions by Diruta and other contemporary composers, followed by the second part in 1609 when serving as an organist in Gubbio. There he had the chance to meet Banchieri, housed at San Pietro monastery, and the two musicians became life-long friends.

Banchieri names the two organs at the Santa Casa Basilica in Loreto (Marche) – the Holy House Basilica – both restored by Baldassarre Bolognese – Baldassarre from Bologna – and played by Francesco Maria Borelli and his nephew. The legend says that in 1294 the house of the Virgin Mary – the Santa Casa – was miraculously brought by angels to a laurel grove in Italy – and so the place was given the name Loreto. The present Basilica, begun in 1468, is one of the most visited Roman Catholic shrines of Italy.

The organ builder is none other than Baldassarre Malamini (ca.1540-1616), born in Cento, Ferrara (Emilia Romagna). He built around 45 instruments and some large 16-foot organs in his home region, some of them still preserved today – e.g. San Procolo church, Bologna (1580) and San Petronio Basilica, Bologna (1596). He used to build flutes in VIII, in XII – called Nazarda – and in XV, as well as Tromboni at the manual. Malamini was active in Loreto in 1567, when he restored, and most probably enlarged, two older instruments.

It is presumable that Malamini restored the two older instruments under the direction of Sebastiano Hay (?-?), a Flemish organ builder and musician who later became the organist at the Basilica. He was quite active as an organ builder in Central Italy, where in 1581 he built a large 2-manual organ at Sant’Apollinare Basilica in Rome (Lazio). A project signed on July 31, 1589, for a new organ at Sant’Agostino church in Esanatoglia, a small village close to Loreto, can provide us with more information: the instrument was commissioned to Malamini, according to a project signed by Sebastiano Hay himself. In this project, the organist describes a medium-sized organ with a short octave keyboard with 45 keys (C-c3), with the following stops:

Principale, Ottava, XV, XIX, XXII, XXIX, Flauto in VIII.

The instrument in Esanatoglia also had the following accessories: Tremolante, Tamburo (drum), Rossignolo (birdcall), Sfiatatore (?, uncertain). It is very likely that one of the two organs at Loreto Basilica would have had a similar structure to this instrument.

Francesco Maria Borelli (1558-1642), was born in Pesaro (Marche) and introduced himself as organist in Loreto in his Il primo libro de madrigali a cinque voci (Riccardo Amadino, Venice, 1599), where he worked between 1592 and 1609. On November 29, 1609, Borelli was appointed cathedral organist in Urbino, as stated in the dedication to him of the motet O quam suavis est from the Sacrorum Canticorum (Giacomo Vincenti, Venice, 1613) by the Milanese composer Serafino Patta (ca.1580-ca.1620). At this moment, nothing is known about Borelli’s nephew who assisted him, and probably succeeded him in 1609, in Loreto.

Continuing his list, Banchieri names the organ at Milan Cathedral, considered noble in character – “[…] uno in particolare magnanimo […]” – played by Guglielmo Arnoni. Milan Cathedral, also known as the Duomo, is one of the most iconic monuments of Italy: the whole building required almost 430 years to complete. It is today one of the largest churches in the world and houses Italy’s largest pipe organ.

The first organ at Milan Cathedral was built by friar Martino de’ Stremidi (?-?) in 1395 and installed in the left transept; a second smaller instrument, most probably a positive organ, was used to accompany the liturgy at the main altar. In 1464, a much larger instrument was commissioned by the Lord of Milan, Francesco Sforza (1401-1466), to Bernardo d’Alemagna (?-ca.1480), placed in the right transept. Bernardo d’Alemagna was an organ builder with German origins who lived and worked mostly in the Venice area. Both the organs were restored between 1490 and 1508.

In 1540, Gian Giacomo Antegnati (ca.1495 – after 1559), member of the prestigious Renaissance organ building dynasty from Brescia, was commissioned to build a new large instrument to replace the Gothic organ from 1395 and to be placed on the left side of the altar. The cathedral confirmed the commission to Antegnati twice – on April 4, 1543 and on January 26, 1552 – and by the end of year 1552, a monumental 24-foot organ with 12 stops was completed, but incredibly it was inaugurated only years later, in the spring of 1579. For a short period, Gian Giacomo Antegnati worked as the cathedral organist in Milan, where he moved with his family. The disposition of the Antegnati organ was as follows:

Principale 24, Principale 12, Ottava 6, XII, XV, XIX, XXII, XXVI, XXIX, XXXIII, Flauto in VIII 6

Another 24-foot instrument, “grosso e stupendo” – large and beautiful – was commissioned to the Milanese organ builder Cristoforo Valvassori (1523-ca.1611), defined a “great and valuable man.” The commission agreement was signed on May 28, 1584, and the instrument was completed in 1590 and placed opposite the Antegnati organ, framed in an identical gilded organ case. The Valvassori organ had a pedalboard and two keyboards with 50 keys (FF-a2) and the disposition of this large organ was identical to the older Antegnati organ – “[…] undeci registri, conforme alli registri principali che sono nell’altro orghano che di presente si usa […]”– with 11 stops, as those in the organ which is now in use – enriched by a second manual with 7 stops. The two organs at Milan Cathedral were played for 36 years, between 1590 and 1626 by Guglielmo Arnoni (ca.1564-1626) – sometimes indicated as Arnone – a Lombard organist and composer born in Bergamo or Milan. He composed books of motets and madrigals, edited between 1595 and 1615.

And now we have come to Bologna, Banchieri’s hometown – “[…] In S. Petronio mia patria […]” – where he names the two organs at San Petronio Basilica, calling them rarities, for their beauty and quality, played by the organists Ottavio Vernizzi and Giovan Battista Mecco. This imposing brick-built medieval church ranks among the greatest of Italy: founded in 1390, the original project would have made this building even larger than San Pietro Basilica in Rome, but its size was scaled down by the church authorities.

San Petronio Basilica’s largest and oldest instrument is a monumental 24-foot organ built between 1471 and 1475 by the Tuscan organ builder Lorenzo di Giacomo da Prato (?-ca.1490), considered the oldest playable organ in Italy, and most probably of Europe. The second one is a 16-foot organ built in 1596 by the already mentioned Baldassarre Malamini from Cento. Both the instruments are still playable today.

With the signature of the construction agreement in April 1471, the building of the new organ started directly in the Basilica, in the chapel of Santa Barbara, which was used as a workshop for Lorenzo da Prato and his assistants. The instrument, with a monumental main 24-foot façade and a rear 12-foot façade, required around 5 years to be completed: unlike today's arrangement, it was then placed in Cornu Evangelii, in front of the same chapel that had been used as a workshop during the years of construction and it is now placed in cornu Epistolae.

On July 1, 1475, the French friar Ogerio Saignand of Dijon (?-?) was hired as the Basilica organist, starting his service in August, confirming that the organ was completed in 1475. Some modifications were introduced by Giovanni Battista Facchetti (1475-1555), famous organ builder from Brescia, who installed a new wind-chest in 1531, by Giovanni Cipri from Cento, who added a second flute stop (Flauto in XII) in 1563 and by the local organ builder Alessio Verati (?-?), who added the Tiratutti in 1852. The keyboard has 54 keys (FF-a2) without FF# and GG#, with sub-semitones for a flat, a flat 1 and a flat 2: the pedalboard has 20 keys (FF–d), without FF# and GG#, and it is constantly coupled to the manual.

Principale contrabbasso 24 (front façade), Raddoppio (a second rank of Principale 24, from c#), Principale 12 (rear façade, two ranks from c#, three ranks from b flat1), Ottava 6 (two ranks from b flat), Duodecima, Decimaquinta, Decimanona, Vigesimaseconda, Vigesimasesta-Vigesimanona, Flauto in VIII, Flauto in XII

Right opposite to the Lorenzo da Prato organ, a new instrument was completed in 1596 by Baldassarre Malamini from Cento. It was slightly smaller than the Lorenzo da Prato organ, with a double façade, both with a 16-foot principal. The instrument was modified and enlarged between the 17th and the 19th centuries; in 1642, Antonio Colonna (?-1666) from Salò, added a second Principale; in 1691, Francesco Traeri (?-1732) from Bologna replaced the keyboard; in 1763, Filippo Gatti (1719-1793) from Bologna replaced the pedalboard; in 1812, Vincenzo Mazzetti (?-?) enlarged the keyboard, added the Voce umana and the Tiratutti. The keyboard has 60 keys (CC-c3) with a short first octave and sub-semitones for d#, a flat, and d#1; the pedalboard has 18 keys (CC-a), and it is constantly coupled to the manual.

Principale I 16 (front façade, two ranks from b), Principale II 16 (rear façade, two ranks from f), Ottava 8, Quintadecima, Decimanona, Vigesimaseconda, Vigesimasesta, Vigesimanona, Flauto in VIII, Flauto in XII, Voce umana (from f)

A long restoration work of these two important instruments was completed in 1974 by Tamburini, Crema, Cremona, under the supervision of the organ expert Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini (1929-2017).

The organist Ottavio Vernizzi (1569-1649) began his service at San Petronio Basilica in 1596 as chapel master, continuing his service as an organist until 1649. Giovan Battista Mecchi (1573-1613) – indicated by Banchieri as Mecco – was a Bolognese organist who worked at San Petronio from 1596: both Vernizzi and Mecchi, who applied for the organist job, were hired in the same occasion, in the very same year when the building of the second organ was completed. The two musicians played together and alternated or substituted each other when needed, as stated in a music chapel statute from 1528. While Vernizzi published both motets and madrigals, Mecchi published a single work, Motecta quinque et octo vocum (Venice, 1611).

When Banchieri was a student in Venice, he surely had the chance to hear and play the organs at San Marco Basilica, two instruments of supreme sweetness – “[…] In S. Marco di Venetia doi di somma dolcezza […]” – played then by Giovanni Gabrieli and Paolo Giusti. San Marco Basilica is a very peculiar church, closer in style to Byzantine and Orthodox churches, mixing elements and decorative styles of East and West to create a sensational monument and one of Europe’s greatest buildings. The first church was founded in 828 by the doge Giustiniano Partecipazio (?-829) to house the relics of San Marco – Saint Mark. Between 978 and 1117 the older church was replaced by a larger Basilica, decorated during the 12th century with 4.240 sq.m. of golden mosaics.

San Marco Basilica in Venice was known all around Europe as the centre of music with its glorious polychoral tradition, a style arose for the peculiar architectural and acoustical qualities of the building itself, where two or more choirs are placed at distance to sing in dialogue a cappella or accompanied by instrumental ensembles. For this practical reason, San Marco Basilica has also featured two organs facing each other, able to accompany the different singing choirs.

The presence of an organ at San Marco is documented in 1316, when an organ builder called Zuchetto (?-?) repaired the organ – or organs – which was in a bad condition – vastadi, wasted: this indicates that the instrument had been in use already for a long time. A new organ was commissioned on June 17, 1364, to Jacobello (?-?): the only request from the commissioners was that the new organ should be bigger than the pre-existing one – “[…] quod organum debet esse potius maius quam minus quam sit ille quod est ad presens in eadem ecclesia Sancti Marci […]”. It is not clear if this instrument was flanked by a smaller instrument placed in the opposite gallery. A second organ appears anyway in 1388, when the Franciscan friar Francesco (?-?) built a further instrument. Both the organs had the same façade layout and were placed opposite in the galleries above the main altar. The organ on the left side had large wooden doors, painted around 1465 by the Venetian artist Gentile Bellini (1429-1507): Saint Mark and Saint Theodor on the external doors and Saint Jerome and Saint Francis on the internal ones.

Between 1488 and 1490, friar Urbano Spiera (?-ca.1516) rebuilt the organ: San Marco’s grand organ was used as an example by other Italian organ builders as the most monumental organ project to be installed in a large cathedral. Giovanni Battista Facchetti proposed this very project for Milan Cathedral and Santa Maria in Vado church in Ferrara – “[…] de la grandezza de quello è in Sancto Marco in Venetia […]” – both proposals dated 1515. Bernardino Vicentino (?-?) did the same for Udine Cathedral in 1516 and Vincenzo Colombi for Sant’Agostino church in Padua in 1528. The German organist and composer Johann Mattheson (1681-1764) visited Venice in 1739 and described the main organ at San Marco in his treatise Der Volkommene Capellmeister (Hamburg, 1739).

From the copy proposals by Facchetti, we know that the 24-foot Principale Contrabbasso was placed inside the organ case and was not visible from the church – “[…] andarano di dre, et non si vederano, essi haverano la prima cana longo 21 pè […]” – and the façade was made with the 12-foot Tenori pipes (=Principale, as called in the 16th century Venetian organ building tradition) – “[…] li quali andarano facti de stagno, et se metterano in facia de l’organo […].” The bellows were 7 and they were placed behind the organ, occupying all the available space. The disposition of the organo grande was as follows:

Principale contrabbasso 24, Tenori 12, Ottava 6, Duodecima, Quintadecima, Decimanona, Vigesimaseconda, Vigesimasesta, Vigesimanona, Flauto in VIII

In 1558, the famous Venetian organ builder Vincenzo Colombi (ca.1490-1574) rebuilt the organ built by friar Urbano, following the indications of the organists at that time, Claudio Merulo (1533-1604) from Correggio and Annibale Padovano (1527-1575) from Padua. Vincenzo Colombi rebuilt in 1595 the second organ, the smaller one, originally built in 1388 by the Franciscan friar: placed in the right-side gallery, it had only four stops but it was renowned for its sweet sound, as described by Banchieri. Merulo asked Colombi to install a Flauto in VIII in this organ, placed on a separated wind-chest.

After centuries of restoration and rebuilding, both instruments were replaced by two new organs built in 1766 by Gaetano Callido (1727-1813), who installed also a third smaller one with five stops. Today, one of the two Callido organs is preserved in its almost original condition; the other Callido was deeply modified in 1893 by Trice & Anelli from Genoa and again in 1972 by Tamburini from Crema (Cremona). The third was lost during the 19th century. Two more Neapolitan organs from the 18th century are placed in a side chapel and in the apse behind the main altar.

Giovanni Gabrieli (ca.1555-1612), eminent Venetian organist and composer, succeeded his uncle Andrea Gabrieli (1532-1585) as organist at San Marco Basilica. The Venetian polychoral tradition is represented in the best possible way in the music written by the two Gabrieli. Giovanni became a student of his uncle and later worked as a chapel musician at the ducal court in Munich (Germany), then directed by the eminent Flemish composer Orlande de Lassus (1532-1594), who had a fundamental role in his composing development. In 1584, he became the organist at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco and substitute organist at San Marco, where he became the first organist one year later. Giovanni devoted himself to publishing his uncle’s compositions, sacrificing time to publishing his own: in 1597 he published his most important work, Sacrae Symphoniae […] (Angelo Gardano, Venice, 1597), a large collection of polychoral works from six to sixteen voices and instruments.

The other musician named by Banchieri when talking about San Marco in Venice was Paolo Giusti (ca.1560-ca.1623), who served as the second organist from September 15, 1591, together with the first organist Giovan Paolo Savi (?-?, hired on July 26, 1610), during the period when the great composer Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) was chapel master at the Basilica between 1613 and 1643.

After Venice, Banchieri names Brescia, a lovely town in Lombardy and second largest of the county, known to be the house of the most important Italian organ building dynasty during the Renaissance, the Antegnati family. The instrument Banchieri names is the Antegnati organ at Brescia Cathedral, a circular-plan church built in the 11th century and known by the names of Santa Maria de Dom or Duomo Vecchio – the Old Cathedral. Banchieri attributes the organ at Brescia Old Cathedral to Costanzo Antegnati – wrongly spelled Constanzo: indeed, this instrument was built in 1536 by another member of the family, Gian Giacomo Antegnati, the very same organ builder who completed the large 24-foot organ at Milan Cathedral in 1540.

In 1464, Bernardo d’Alemagna built a new instrument at Brescia Cathedral – which was the only cathedral in Brescia at that time, probably rebuilding a pre-existing instrument present at the cathedral at least from 1432. Bernardo d’Alemagna’s son, Antonio Dilmani (?-ca.1500), rebuilt his father’s instrument in 1481 and in 1482, Bartolomeo Antegnati (?-?) repaired it after some fire damage, working there again in 1494. An organ builder from Piedmont, called Giovanni da Pinerolo (?-?) built a new organ with 7 stops in 1514, and between 1536 and 1538, Gian Giacomo Antegnati built the organ named by Banchieri. The commission agreement for this marvellous instrument was signed on October 20, 1536, and it gives a lot of information about the characteristics, among others a 50-key short octave manual (C-f3), a pedalboard with 20 notes (C-b) with a separate wind-chest for the basses – “[…] Et si obliga di far un somero da sua posta per quelle seconde principale tanto quanto tiene il pedale […]” – 5 good bellows, spring-chest and the following disposition:

Principale I, Principale II, Ottava, Quintadecima, Decimanona, Vigesimaseconda, Vigesimasesta, Vigesimanona, Flauto in VIII, Flauto in XII, Cornamuse (?), Cornetto (?).

These two last stops are indicated in the agreement as a new kind of stops – “[…] dui registri de una nova foza de canne qual canne saran cento qual faranno varij soni como sarra cornamuse, cornetti et simile […].” Two large wooden doors were painted in 1540 by the artist Girolamo Romani (ca.1485-1560), known as Romanino. Already restored and modified during the 17th century, the Antegnati organ was enlarged in 1826 and 1829 by the Serassi family from Bergamo, who altered the stoplist of the instrument integrating new stops to the old ones and maintaining the 16th century pipe material. The instrument is in the moment (January 2021) being restored by the Mascioni organ company from Cuvio (Varese).

Although his attribution about the organ in Brescia is inaccurate, Banchieri names the talent of Costanzo Antegnati both as an organist and organ builder in regards to another instrument, this time correctly attributed: praising Antegnati as an excellent organist and organ builder – “[…] organista & organaro eccellente […]” – as proved by the organ at Verona Cathedral, played by Paolo Masenelli.

Costanzo Antegnati (1549-1624) began his career as an apprentice of his father, the famous Graziadio Antegnati (ca.1525-ca.1590). After a first period as his father’s assistant, Costanzo signed many instruments between 1588 and 1615, among others those for San Nicola church in Almenno San Salvatore, Bergamo (1588), San Giorgio church in Bagolino, Brescia (1590), Santa Maria della Steccata Basilica in Parma (1593), San Gaetano church in Brescia (1596), Sant’Agostino church in Bergamo (1607), San Giorgio Maggiore Basilica in Venice (1612). Remembered today both as an excellent organ builder and as a gifted composer, Costanzo described the long family business in L’Arte Organica, published in Brescia in 1608, probably completed in 1600 upon the request of the nuns at Santa Grata church in Bergamo. This short treatise in the form of a dialogue between father and son - Costanzo in the first person and his son Giovan Francesco (1587-1630) – represents the most direct source both to know the work of the Antegnati as organ builders and the approach to the Italian organ practice during the Renaissance period: after solemnly affirming that this activity is “[…] by nature truly liberal and worthy of a noble man […]” – per natura sua veramente liberale e degna di huomo nobile – he proudly recalls his ancestors and lists approximately 140 instruments built in their workshop. Continuing with the dialogue, Costanzo illustrates the practical rules for tuning the organ and other early keyboard instruments. One of the most important parts of the treatise is the last chapter about organ registration, where he gives advice about how to use the Ripieno, the Fiffaro and the flute stops. Banchieri remembers Costanzo Antegnati as an excellent organist: in fact, he was appointed cathedral organist in Brescia – at the organ he built himself – on July 16, 1584, a position that he occupied for around 20 years. Among his works, L’Antegnata: Intavolatura de Ricercari d’organo (Angelo Gardano, Venice, 1608) containing twelve ricercari for each of the ecclesiastical tones.

Verona Cathedral, the main church of the Diocese of Verona, was built from 1139 in Romanesque style and completed in Renaissance style during the 16th century. A medieval organ was documented in 1378 when the instrument needed some bellows reparation. At the end of the 15th century, the local organ builder Nicola Pomei (?-?) restored the instrument, which was rebuilt by a Flemish organ builder, Ludovico Arnold (?-?) a few years later. The organ Banchieri names in his Conclusioni is the new instrument commissioned in 1608 by the Cardinal Agostino Valier (1531-1606), bishop of Verona, to the famous Costanzo Antegnati. The new instrument was placed in a gallery in cornu Evangelii. Another instrument to be placed in cornu Epistolae was later commissioned to Giovanni Berté (1560-1632) from Brentonico (Trento), who had an organ building workshop in Verona. After a time of changes when the organ builders did not intend to restore the instrument authentically but modernizing it according to the musical taste of the time, in 1909, the Veronese organ builder Domenico Farinati (1857-1942), built a new instrument to replace the Berté organ but placing it on the opposite side. Of the old Antegnati organ, moved then to the gallery in cornu Epistolae, only the façade pipes were salvageable. The present instrument is an historical copy of the original Antegnati organ built in 1991 by Bartolomeo Formentelli from Verona, reutilizing the original façade. The disposition is as follows:

Principale 12 (bass/treble), Ottava 6, Decimaquinta, Decimanona, Vigesimaseconda, Vigesimasesta, Vigesimanona, Flauto in Ottava 6, Flauto in Duodecima, Flauto in Decimaquinta, Fiffaro 12 (treble), Piva 8 (reed, treble), Tromboncini 8 (reed, bass), Contrabassi 16 (pedal). Tremolo, Usignoli.

Paolo Masanelli (1551-1613), the organist who Banchieri names in Verona – actually named Masnelli – was a Veronese musician, quite well-known and appreciated as a composer of madrigals – Madrigali […] libro primo (Angelo Gardano, Venice, 1582). Around 1583, Masnelli was active as a court organist in Mantua, where he worked until 1592. Masnelli worked as the cathedral organist in Verona from 1593, as well as the organist at the Accademia Filarmonica.

In his tour of the best Italian organs of his time, Banchieri moves from Verona to Tuscany, where he names two instruments built by the Cortonese organ builder Cesare Romani, considered by Banchieri “an expert in the art of organ building” – “[…] consumato nella professione di fare Organi […]”. Among the many organs built by Cesare Romani, Banchieri choses to name two instruments considered of supreme perfection – “[…] di somma perfettione […]”: one at Pistoia Cathedral and the other at Monte Oliveto Maggiore Abbey.

Descendant of Luca di Bernardino – who was the brother of his grandfather – Cesare Romani (1544-1616) is considered today one of the most important names in the Cortonese organ building school and the leading exponent of the great dynasty Cianciulla-Romani. The organ built by Cesare Romani in 1590 for Pistoia Cathedral was played for the first time on January 6, 1591.

The organ at the Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore in the Siena area is certainly one of the best examples of Cesare Romani’s work. Although the original construction agreement has been lost, the organ was built in Cortona between 1606 and 1607. By the end of December 1607, the instrument was already installed and playable and the payments for the new organ are recorded from the following year. Banchieri held Romani’s work in high regard and the respect that he showed for the organ builder from Cortona is very evident. Banchieri also inaugurated the new instrument and became the first organist.

Contrary to the practice of the time, the organ builder built the organ in Cortona and then moved it later to be installed in the intended place. Following the temporary closure of the Abbey in 1810, the organ was moved to the collegiate church in San Quirico d'Orcia; thanks to the interest of the Marquis Flavio Chigi (?-?), who presented to the Chapter of the collegiate church the idea of buying the organ from the now abandoned abbey. The Chapter accepted the proposal and the organ was installed on the back wall of the presbytery above the wooden choir, where it still stands today. The instrument, damaged during the Second World War, was recently restored in 2011 by Nicola Puccini from Migliarino, Pisa. The short octave keyboard is new and has 45 keys (C-c3); the short octave pedalboard, rebuilt, is constantly coupled to the manual and has 8 keys (C-H). The wind-chest and most of the pipes are original. The actual disposition is as follows:

Principale 8 (two ranks from b flat), Ottava 4 (two ranks from b), XV (two ranks from b), XIX, XXII-XXVI, Flauto in XV

Banchieri does not forget to name Luca Perugino – Luca from Perugia – none other than Luca Blasi who built a monumental organ at San Giovanni in Laterano Basilica in Rome. This instrument was so appreciated by Pope Clemente VIII (1536-1608) that the organ builder was knighted – “[…] Ne si deve tacere Luca Perugino, che così industriosamente fabricò un Organo in S.Gio. Laterano per lo cui valore, da Papa Clemente 8 ottenne ordine di Cavalliero […]”.

Luca Blasi (1545-1608), sometimes called by the name Biagi, was originally from Perugia. He was an apprentice of Vincenzo Fulgenzi. Blasi was active in the Roman area, but also in his hometown Perugia, Spoleto, Orvieto and Sulmona, where in 1602 he built a large 16-foot organ for the Santissima Annunziata church. Blasi sometimes used to introduce himself as Papal organ builder – “[…] Magnificus Dominus Lucas Blasius perusinus Sanctissimi Domini Nostri Papae organista […]”, as in the commission agreement for the organ at San Giovanni church, Marino (Rome), dated January 5, 1607.

The famous instrument built by Blasi for San Giovanni in Laterano Basilica was built between 1597 and 1599, on time for the 1600 Jubilee celebrations. This large basilica was founded already in 313 but was rebuilt in the present form during the 17th century. Under the Middle Ages, the basilica was the most important church in Rome and was elected as the Cathedral of Rome: in fact, even if known as the Lateran Basilica, it is still today Rome Cathedral, seat of the cathedra of the Bishop of Rome, the Pope. The original instrument was based on a 24-foot principal placed in façade, with sub-semitones, ripieno up till the XXXVI, double ranks for the highest ranks, two flute stops, two reed stops – zampogne and trombe – and tremolo. No other Italian organ was as big as this instrument, “[…] che nessuno ce ne è di questa grandezza […]”.

Imposing for its time, this instrument has two manuals: the upper manual has 66 keys (FF-f4) with sub-semitones for a flat, a flat 1, a flat 2, d#1, d#2, d#3; the lower manual, added lately, has the same extension FF-f4, without sub-semitones with the real compass C-f4. The pedalboard, constantly coupled to the upper manual, has the compass FF-f with two sub-semitones.

Enlarged during the 18th century, first in 1731 by Celestino Testa (?-?) and Ugo Annibale Traeri (1689-ca.1735), then in 1747 by Lorenzo and Antonio Alari (?-?). Completely restored between 1985 and 1989 by Bartolomeo Formentelli from Verona, this magnificent instrument can still be seen and is regarded as the oldest playable organ in Rome.

Primo Organo (Upper Manual): Principale profondo 24 *, Principale profondo 24 **, Ottava 12, XV 6, XIX, XXII, XXVI, XXIX I (?), XXIX II (?), XXXIII I (Alari), XXXIII II (Alari), XXXVI I (Alari), XXXVI II (Alari), Flauto in VIII 6, Flauto in XV, Tromba 12 (Formentelli), Tremolante (Formentelli)

Secondo Organo (Lower Manual): Principale 8 (Traeri), Ottava 4 (Alari), XV 2 (Alari), XIX (Alari), XXII (Alari), XXVI (Alari), XXIX (Alari),, Flauto in VIII 4 (Alari), Flauto in V 2 2/3 (Alari), Flauto in XV 2 (Formentelli), Cornetto 2 file (2 ranks, Alari and Formentelli), Tromboni 8 bassi (bass, Formentelli). Tiratutti. Uccelliera.

*= inserting the façade pipes. **= inserting the rest of the pipes inside the organ case.

Banchieri continues his list of names and instruments mentioning Andrea Ravani, called by Banchieri Andrea Luchese – from Lucca – and his beautiful organ recently completed for San Ponziano church in Lucca – “[…] Andrea Luchese, il quale ultimamente ha fabricato uno Organo stupendo in S. Pontiano sua patria […]”. Sadly, this organ no longer survives today: the organ gallery preserves a monumental empty organ case, most probably the original one. As we can deduce from Banchieri himself, this organ was built right before 1609, the date of publication of the Considerazioni. A much smaller instrument was placed in the empty case during the 18th century, in turn empty and devoid of all the pipes.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the brothers Andrea (1575-1616) and Cosimo Ravani (1584-1635) managed to bring the centre of Tuscan organ building back to Lucca, earning a reputation that led them to work for the major basilicas in Tuscany, Rome and the Catania Cathedral in Sicily. The two brothers learnt the art of organ building with the Venetian organ builder Vincenzo Colonna (1542-1582) when he was building the organ for Lucca Cathedral between 1590 and 1593. Andrea Ravani built some organs in the Lucca area and a 12-foot organ for Santa Maria del Carmine church in Pisa (1613). The two brothers together built a masterwork for their hometown, a large 12-foot organ for Lucca Cathedral between 1610 and 1618.

Concluding the fourth Conclusione, Banchieri names some musicians: Luzzasco Luzzaschi (organist at Ferrara Cathedral), Claudio Merulo (organist at Parma Cathedral), both of them worthy of eternal memory – “[…] Devo però far menzione di dui Organisti cellebri, le cui anime sieno in Gloria, Luzzasco Luzzaschi fù nel Duomo di Ferrara, & Claudio Merulo in quello di Parma, amendui suggietti degni di memoria eterna […]”.

Luzzasco Luzzaschi (ca.1545-1607) was originally from Ferrara, at that time one of the most powerful and culturally rich towns of Italy. This small town was ruled for centuries by the Este dynasty: the noble family took control of the town in the late 13th century, ruling Ferrara until 1598, when the papacy forced the family to move to Modena. The great Este castle looms over the town centre together with the 12-century cathedral, one of the largest in Italy. Luzzaschi began his career as a musician at the Este court, where he worked as a chapel musician, first as a singer from 1561 then as first organist in 1563. On September 30, 1572, he was appointed cathedral organist in Ferrara, a service he held until his death. Luzzaschi was a great virtuoso and became famous for his madrigals, published in numerous books: his fame today is linked to the name of Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643), the greatest Italian organist of the time, who was his fellow-citizen and most famous pupil.

Claudio Merulo (1533-1604), also known as Claudio Merlotti – his real surname – was among the most famous organists of his time. He was born in Correggio, a village nearby Parma, a ducal town with fine medieval buildings. Merulo became first organist at San Marco Basilica in Venice on July 2, 1557, and he hold this position until 1584. He returned to Parma at the service of the Farnese ducal family as organist at the Cathedral – from 1586 – and at Santa Maria della Steccata Basilica, where he was appointed on October 1, 1591. Merulo published books of toccate and ricercari, contributing with numerous masterworks to the Italian keyboard repertoire. He was also a gifted organ builder: the 4-foot positive with 4 stops he built in Parma is still in use at the Parma Conservatoire of Music.

The very last thought is reserved to Gioseffo Guami, defined by Banchieri as an excellent composer and very sweet organ player. Banchieri reserves this last praise to his master, complimenting his compositions and his service as an organist at San Marco in Venice. Banchieri remembers also Gioseffo’s sons, Domenico and Vincenzo, two extremely gifted young musicians – “[…] gli quali in giovenile età rendono stupor à chi gli gusta […]”. Remembering Gioseffo Guami, Banchieri names also Domenico di Lorenzo da Lucca, who built an organ very a sweet sound – “[…] organo soavissimo […]”– at Lucca Cathedral, where Guami was the organist.

The composer Gioseffo Guami (1542-1611) – sometimes called Giuseppe Guami – deserves a prominent place among the many musicians who served as organist at Lucca Cathedral, even if mainly remembered today for his service as organist at San Marco Basilica in Venice. Banchieri again expressed his high esteem towards the master from Lucca calling him a very particular man with vivacity of hands as well as in the publication of his Concerti ecclesiastici a otto voci (Venice, 1609) where he proudly presented himself as disciple of Mr. Gioseffo Guami. Born in Lucca to Domenico da Guamo (?-?), silk maker, Gioseffo studied music in the same hometown. More studies brought Guami to Venice where he studied under the guidance of Adriano Willaert (1490-1562), chapel master at San Marco Basilica. Guami may have begun his studies in Venice around 1557 as some of his compositions appear in anthologies published in Venice in 1562. Directly involved in the musical activity at San Marco, he met the famous Flemish composer Lassus who recruited him as an organist together with his brother Francesco (1543-1602) – who was a trombonist – to play at the court chapel in Munich, where Lassus was appointed as chapel master. From 1568 to 1570 as well as from 1574 to 1579 he was active as a paid organist in Munich, despite having received in December 15, 1574 the appointment as organist – under a period of three years – at San Michele in Foro church in Lucca, a job that he never took.

Guami was still admired and remembered in Venice after his period as a Willaert’s student as a famous organ virtuoso. In June 1, 1588, the priest Francesco Sugana, singer and substitute chapel master at San Marco Basilica, presented the name of Guami to the commission who was looking for a new Basilica organist: [...] I have never found a more valiant and deserving musician than Mr. Gioseffo Guami from Lucca [...] that he did not have to yield to anyone else in Europe [...] for the singing and the playing [...], putting the name of the famous musician and scholar Gioseffo Zarlino (1517-1590) as a reference in the event of a practical audition for the post of organist. The appointment as first organist came on October 30, 1588, when Zarlino was the chapel master and Giovanni Gabrieli the second organist. The post in Venice did not last very long – the contract ended on September 15, 1595 – and in 1590 he returned to Lucca, where on February 27, 1591 he was appointed cathedral organist. In 1592 he became the music teacher of Adriano Banchieri. Guami died in Lucca in December 1611.

In his instrumental compositions, there is a growing autonomy from vocal models, in favour of a language gradually oriented towards the characters of the concertato style. The canzoni reveal original creative ideas in the conduct of the voices – among the best known, la Guamina. In the keyboard works there is a stylistic proximity to the compositions by Gabrieli, albeit in a shorter and more compact form; the influence of Lassus is quite evident in his vocal compositions, where Guami’s motets differ, in the form with eight or more voices, from the Venetian double choir model, manifesting a closer relation to compositions by the Flemish master. Belonging to a family of musicians, Gioseffo’s sons Vincenzo (?-ca.1614) and Domenico Guami (1583-1631) were organist too at Lucca Cathedral between 1612 and 1631. Both them composed motets and were succeeded at the cathedral by their other brother Valerio (1587-1649).

The very last organ builder mentioned by Banchieri in his fourth Conclusione is Domenico di Lorenzo da Lucca (1452-1525): also known as Domenico degl’Organi or Domenico da Lucca, Banchieri calls him Domenico Nardi from Lucca. He was considered one of the most renowned Tuscan organ builders of the Renaissance period; in fact, he was not only active in his native region but also in Padua, Lodi, Venice, Viterbo and in Rome as a builder of the organ at the Vatican basilica. Born in Lucca by master Lorenzo di Domenico (?-?) – the organ builder Lorenzo degl’Organi – he probably learned the first fundamental principles of organ building from his father. Domenico’s brothers Luca (?-?) and Nicola (?-?) were also organ builders. The commission agreements for the organs at Lucca Cathedral were useful in defining the three instrument designs that Domenico di Lorenzo used to build depending on the size of the church:

- a 6-foot instrument with a 38-key keyboard (e.g. Santi Giovanni and Reparata church in Lucca, 1481 and San Pier Maggiore church in Lucca, 1495);

- a 12-foot instrument with a 47-key keyboard (e.g. Lucca Cathedral, 1480, Siena Cathedral, 1508, and the Santissima Annunziata Basilica in Florence, 1509, where the keyboard is expanded to 50 keys);

- instruments with a larger design, based either on a 16-foot principale, with a 55-key keyboard (e.g. Sant’Antonio Basilica in Padua, 1480), or on a 16-foot with 50-key keyboard or on 24-foot with 47-key keyboard, both as planned for the second organ for Lucca Cathedral.

After some commissions in Padua – which constitute the first documents in his name – Domenico di Lorenzo returned to his hometown Lucca to build a new organ for the cathedral, as defined in a contract dated the 20th of October 1480, and was payed 450 large gold ducats – the price, however, also included the organ case with decorative carvings and ornaments. The contract specified the requirements and most of the technical characteristics: the major pipe had to be six and a half arms long (12 feet), 47 keys for the keyboard without FF# and GG# with the terzo ordine – the sub-semitones – 5 stops and the pedals connected to the first manual keys, according to a custom prevailing in Italy until the end of the 16th century. The construction of this instrument had to be quite quick: the instrument was delivered by the end of year 1483 and the final receipt was signed on January 13, 1484. The disposition was as follows:

Principale 12 (two ranks from c1, three ranks from c2), Ottava 6 (two ranks from c1), XV, XIX-XXII-XXVI-XXIX (in a single stop), Flauto in XV

The commissioners – representatives for the Opera del Duomo – were so satisfied with the excellent outcome of this instrument that shortly after, on April 7, 1484, they entrusted the organ builder with the construction of a second organ, which was rather curiously agreed upon in an alternative way both on the basis of 16-feet and 24-feet, for a fee respectively of 275 or 450 ducats in addition to the old organ still existing in the cathedral, of which the delivery took place on the following May 13. A period of four years was set as the deadline. On May 31, 1488, the organ builder and the Opera del Duomo proceeded by mutual agreement to the rescission of the contract for the construction of the second organ: evidently Domenico di Lorenzo had too many commissions to work at the same time. He built organs for Pisa Cathedral (1489), Siena Cathedral (1508-11) and his masterpiece is preserved at Santissima Annunziata Basilica in Florence, monumental 16-foot instrument built between 1509 and 1523.

In his fifth Conclusione, Banchieri describes the “modern instruments” – Organi particulari modernamente introdotti con variati stromenti. Here he names the instruments that were famous for their special features, such as reed stops, effects, drums, cornets, and so on. The first instruments he names are two large organs worthy of great praise built in the region of Umbria by the Flemish organ builder Vincenzo Fulgenzi for Orvieto Cathedral and San Pietro church in Gubbio. Banchieri points out the authenticity of the imitative stops and credits to Fulgenzi the introduction in Italy of the Rückpositiv, typical feature of the Flemish organ building tradition.

Vincenzo Fulgenzi (?-?) or Beltrami, Quemar, or Fiamengo as called by Banchieri, was an organ builder with French or Flemish origins. He opened his organ building workshop in Recanati and was mostly active in Central Italy: Cagli (1577), Gubbio (1580), Metelica (1585), Civitanova Marche (1586), Città di Castello (1588), Orvieto (1591).

The first instrument which is named is the organ at Orvieto Cathedral, played by Giovanni Pizzoni (or Piccioni, 1548 – after 1619) from Rimini, who served as an organist at the cathedral between September 20, 1586 until December 31, 1591. This large instrument, with two manuals and Rückpositiv, based on a 24-foot principal, was built between 1579 and 1602: originally commissioned to the Tuscan Domenico Benvenuti (?-1591), it was completed by Fulgenzi. It was commissioned with the ripieno from Principale 24 to XXIX, an open flute, a stopped flute, tromboni, a reed voce humana, tremulant. Fulgenzi enlarged the ripieno, reaching the XLVII and adding many other colourful stops, mainly flutes, reeds and effects.

The second instrument built by Fulgenzi named by Banchieri is the organ at San Pietro church in Gubbio, completed between 1578 and 1598. Banchieri describes its variety of stops: 12 entire ripieno stops plus stopped, open, spitz and conical flutes, trombones, trumpets, regals, cornets, viols and drums, cimbaletti (zimbelstern), birdcalls, tremulants. The magnificent organ case frames today a modern organ built in 1959 by Tamburini, Crema (Cremona), with 2 manuals and 18 stops. Organist at this instrument was Crisostomo Rubiconi (?-?), as stated by Banchieri: nothing is known about this organist.

Among the most peculiar instruments of Italy, Banchieri describes an instrument built by the ingenious Domenico da Feltre (?-?), who apparently travelled around Italy with a mechanical organ with wooden pipes, able to imitate woodwinds, cembalo, strings, brass, cornets, etc. There was also a basin filled with water imitating the Venetian atmosphere with gondolas and ceremonial boats. Not everything in the description given by Banchieri is easily understandable: what is certain is that this instrument was an exceptional entertaining machine – “[…] Quivi appresso devesi far mentione di un’altro ingenosissimo Organaro, Domenico da Feltre, che pochi anni sono scorreva per le Città d’Italia con un’Organo di canne in legno, nel quale suonando con leggiadria un Arpicordo, faceva sentire ogni stromento da fiato, Plettro, & Arco & dentro un vacuo pieno d’acque fingendo gli duo scastelli posti nelle lagune di Venetia, faceva comparire infinite Barche, & Gondole con variati concerti di Lauti, Cithare, Aripicordi, Viole, Violone, & altri […] di nuovo udivasi un concerto di Tromboni, & Cornetti, con un ripieno di diversi stromenti accordati insieme, che rapivano gl’audienti per l’allegrezza, & quello, che rendeva estrema meraviglia, à gl’intendenti, sentivasi un’Organo di diece piedi, con il Mi, Re Ut, & Pedali trasparenti […]”.

Another interesting instrument, more traditional than the peculiar mechanical organ built by Domenico da Feltre, was the 20-foot high organ at Pisa Cathedral. Banchieri describes it like a castle – “[…] fatto à guisa di Castello […]” – with a lot of new inventions such as a Rückpositiv, vaguely described by Banchieri as a detached division placed at the organist’s back – “[…] per quanto mi vien detto ha un Organetto da concerto dietro le spalle dell’Organista separato dall’Organo grosso, & questo suonasi con una istessa tastatura […]”.

The builder of this instrument, unknown to Banchieri – “[…] fabricato ultimamente da un Fiamengo il cui non à me non è noto […]” – was the Flemish organ builder Giorgio Steininger (?-?) assisted by the Tuscan Francesco Palmieri (?-?) from Fivizzano: the two organ builders started the building of the new instrument between December 1596 and 1599.

The two keyboards had a different number of keys: the main organ had a short octave manual with 53 keys (CC-a2) or a 58-key enharmonic keyboard; the manual for the positive probably had 45 keys (C-c3) with a short first octave like the Roman organ. This could have been the disposition:

Organo Grosso (Great): Principale 16, Ottava 8, XV, XIX-XXII, XXVI-XXIX, Flauto (4-foot?), Trombone 8

Organo Piccolo (Positive): Ottava organo grosso 8, Principale 4, Flauto 4, Flauto 2, Flauto in XII 1 1/3, Voce Umana 8 (reed)

Vincenzo Colonna modified the disposition already in 1605 upon request of the cathedral organist Antonio Bonavita (1548-1617). A few years later, the Ravani brothers from Lucca made another big intervention, followed by another one in 1618-9 by Simone Vasconi (?-?) from Florence. The organ was replaced during the 19th century.

The last two instruments named by Banchieri in his fifth Conclusione are two organs in private institutions: the first was in Bologna, owned by Massimiliano Bolognini (?-?) – Banchieri does not provide any more information about it; the second was in Lucca, owned by Tomaso Raffaelli (?-?), in use at Raffaelli’s Academy. This organ, built by Andrea Ravani, had wooden pipes, with sub-semitones and F# and G#. According to Banchieri, this instrument was highly praised by many organists – “[…] stromento comendato da gli professori universalmente […]”.